The world leaders meet today and tomorrow in New York for the United Nations for Refugees and International Migrants Summit. An unprecedented global refugee crisis is the driver for such a gathering and the call for a radical reform of the global refugee regime – starting from (but luckily with little traction) the very definition of who counts as a refugee. The illustration below by the UN for Refugees and International Migrants PR office is meant to convey this urgency.

Everyone (in the West) is familiar with the tragic stories and images of boat migrants making treacherous journeys across the Mediterranean. Time and again we have heard of the horrible death toll in the Mediterranean – more than 10,000 people died making one of those crossings since 2013.

But how global is this crisis really? And is this really a crisis? And why does it matter? For one, to understand why the call from the EU states for the international community to take more refugees has received a less generous response than they had hoped for.

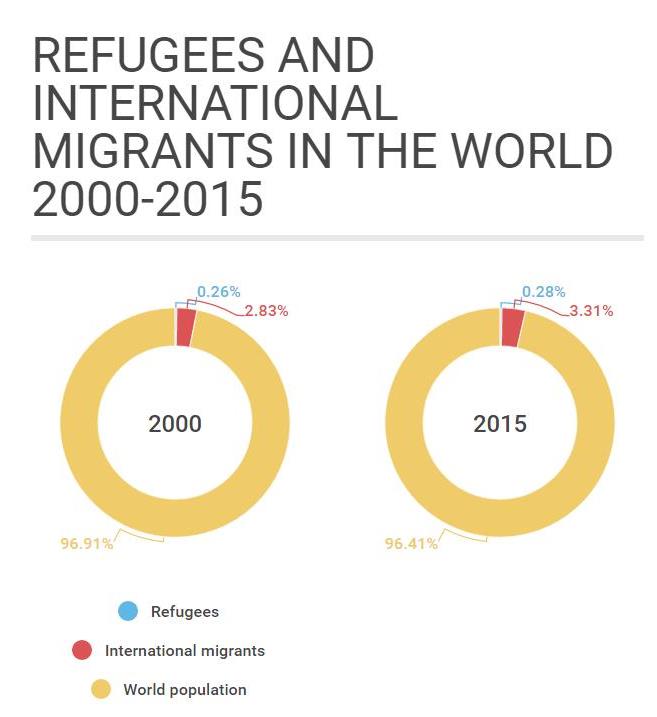

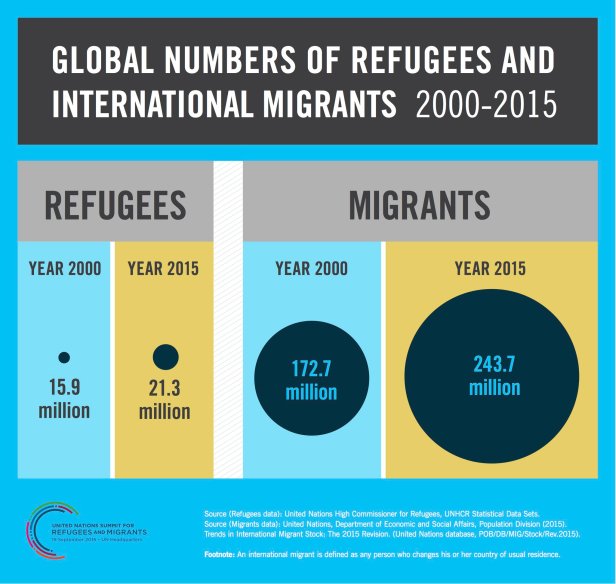

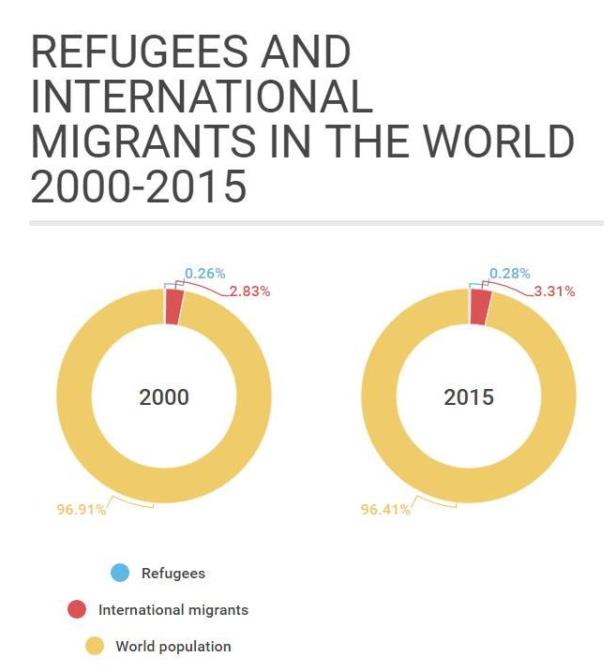

The following visualisations may help to put things in perspective. First, while the number of refugees and international migrants is indeed increased, so has the population of the world. The current so-called global refugee crisis affects only 0.28% of the world population, fifteen years ago the quota was 0.26%. Similarly, international migration has increased in absolute terms but it still counts only for 3.33% of the world population, it was 2.83% fifteen years ago (and I’m leaving aside any discussion on the reliability of data and how data collection has changed over this period).

But why is not everyone keen to help the EU to cope with the inflow of refugees by relocating refugees from there*? Perhaps because it is hard to justify why a country which has a limited number of resettlement places should prioritise the relatively few refugees currently settled in one of the wealthiest regions of the world instead of those parked in refugee camps for years in much poorer countries.

Going back to the graph above it is also puzzling why a Summit like the one they are holding in New York today is even happening – why are migrants and refugees all gathered in the same basket?

I’m well aware of the mixed migration / mixed motivations debate – this is in fact one of the core issues we discuss in the MEDMIG research brief on the Central Mediterranean route released today – but the point here is that by linking up together Refugees and Migrants in the same forum is implicitly endorsing the idea that migration is a problem or that migrants have problems. People that saw a graph such as the one produced by the UN for Refugees and Migrants PR office is easily misled to think: ‘Oh God! there are so many people that need our help’ (if they are progressive/liberal), or ‘Oh God! It’s an invasion we need to build an enormous wall all around us‘ (if they are conservative/nationalist). Both positions are wrong, the overwhelming majority of those 200 million people who are international migrants are just fine without UN’s help and happily carry on with their life. They remit money to their loved ones, teach in our schools and universities, run our health services, marry our Deputy Prime Minister (Nick Clegg) or the former leader of anti-immigration party (Nigel Farage). And yes, sorry, I’m one of them. The conflation of migrants and refugees is potentially dangerous and hardly workable. While there is a degree of overlap this is tiny, it is crucial to keep things in perspective. This is why we should be careful with how we imagine and visualise international migration.

*Malta is the only EU states that resettle refugees under the quota scheme in the US.